A Force for Change: Courage in the Face of Oppression

A Force for Change: Courage in the Face of Oppression

Our deepest gratitude to Renewal Care client Kenneth Mannings for sharing his story with us.

by Russell Weigandt

Kenneth Mannings.

When you first talk with Kenneth Mannings, it becomes immediately clear that he sets a very high bar of achievement for himself. But despite retiring as an administrative law judge in NYC, working for former President Jimmy Carter when he was governor of Georgia, and participating on the front lines of the civil rights movement in support of Martin Luther King, Jr., Kenneth describes his past with a casual nonchalance. His humility belies his deep wellspring of strength and courage, which he has drawn upon to overcome oppression and sustain his lifelong commitment to social justice.

Kenneth was raised in Tuskegee, AL, and Atlanta, GA. He was the oldest of three sons, and his parents were both doctors. In fact, his mother was the first Black female doctor to be board certified in internal medicine in the entire nation.

Kenneth’s family was very connected with political and civil rights leaders in Atlanta. CNN actually ran a segment on his grandmother, who had lived through the entire progression of the civil rights movement. In 2008, at the age of 106, she finally had the opportunity to cast an early vote for a Black man for president. Barack Obama saw the segment and even called her from the campaign trail.

During Kenneth’s childhood in the 1950s and 60s, Jim Crow laws ensured that “separate but equal” segregation was ever-present. At that time, many banks across the nation had “redlined” Black neighborhoods, prejudicially classifying them as too risky for loans. His grandfather, however, ran a successful dentistry practice in Atlanta and sat on the board of a local Black bank—so he was able to secure a mortgage. He even helped Kenneth’s mother purchase a home in a middle-class neighborhood.

His grandfather also owned a number of rental properties until he was forced to sell them in the face of pressure from the IRS, which often targeted wealthy Black individuals during this period. One day while cleaning the gutters, his grandfather had his first heart attack and fell off the roof; his family attributed his condition to the stress of dealing with the IRS.

Despite being surrounded by constant reminders of racism and discrimination, Kenneth excelled in school and had built quite the resume by the end of high school. Not only was he the class valedictorian – like both of his parents – he was also the editor of the yearbook, a writer and designer for the school newspaper, and a member of the debate team, the science club, and the drama club, among other extracurriculars.

Kenneth actively participated in the civil rights movement as well. After Martin Luther King, Jr., was arrested and held in jail for demonstrating without a permit in Albany, GA, Kenneth was excused from high school with his friends to participate in an Atlanta march protesting his imprisonment. They ended up walking right alongside Martin Luther King, Sr., in the front of the march, and made it on the evening news for two of the three local news channels.

“We felt like we were helping to make history,” he recalls. “It was a big deal for us.”

Even though he found solidarity participating in the civil rights movement, racism had a physiological impact on him. He believes that all the anxiety and stress he held inside is largely why he’s had high blood pressure since he was just 15 years old.

In addition to being a Black man growing up in the South, Kenneth was also a gay man growing up in the South. The intersectionality of his identity meant that he needed to contend with both widespread homophobia and overt racism – often at the same time.

He vividly recalls being targeted with slurs and physical violence while attending a summer pre-college program at Morehouse College, one of Atlanta’s historically Black colleges. On his way back from a drug store one evening, he was attacked by a mob of male program participants who were dressed up like Klansmen, with hoods on their heads and paper bags over their faces with eyes cut out. They surrounded him, yelled homophobic slurs he’d never heard before, and attacked him with baseball bats and two-by-fours with nails in them.

“Some of us had to fight not to be crushed and stamped down by those who wanted to hurt us,” Kenneth recalls painfully, noting that he was already 6’2” at the time. “I was furious. I bested them, and, ultimately, they ran off. That’s when I first realized how bad homophobia could be.”

The perpetrators later dragged one of his friends out of his dorm room and taunted him in the hall in front of everyone. These traumatic encounters left a deep psychological scar and exposed the seriousness of the risk of being outed. Looking back today, Kenneth believes that the leaders of the mob, two kids from the Bronx, NY, were likely gay themselves, and had attempted to use him and his friend to deflect attention from their own sexual identities.

These fears of being “found out” continued to haunt him throughout college, law school, and his professional career. In those contexts, he kept his sexual orientation hidden, because he knew that being outed could lead to fairly dire consequences.

“Nobody who succeeded in life then was openly a homosexual,” recalls Kenneth, who described being gay as the “big secret.”

Ultimately, the first person he came out to was a gay, Black classmate at Notre Dame named George from Mobile, AL. They grew close partially because they had both endured similar kinds of oppression in the South. While in Mobile, George was a member of the first ninth grade class to integrate in high school. On his way into the school on the very first day, a White protestor openly shot him in the stomach.

“Seeing that scar on his stomach was more important than what happened at Morehouse,” explained Kenneth. “It made me feel like I needed to be more courageous in how I was living, because he nearly gave his life just to go to school. That affected me deeply.”

Unfortunately, after George was exposed as gay, he was expelled from Notre Dame. While Kenneth kept his sexual identity mostly hidden on campus, he did channel the strength that George showed him by breaking new ground for Black students during his four years in South Bend, IN.

He joined Notre Dame’s Student Union and organized student activities. As the deputy director of special projects, he worked to advance the student body’s understanding of Black culture in America. He brought the production of To Be Young, Gifted and Black to Notre Dame and its sister school, Saint Mary’s. This was the first time a Broadway production had been featured on either campus. Working with several other students, he also lobbied for and organized the university’s first Black Arts festival, which included Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

He also invited Black American poet and author LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka, to do a reading on campus. At the writer’s request, White attendees, including faculty members, were prohibited from sitting in the first five rows. The requirement was a deeply symbolic gesture, which Kenneth described as reminiscent of “the old days when the Blacks had to sit in the balcony and the whites sat in the orchestra.”

“I had some misfortunes in being picked on and called a sissy and all that, but, at the same time, I brought some enlightenment to the place,” said Kenneth, reflecting on his achievements. “I really did help bring enlightened African American culture that had never been there before.”

Kenneth at his desk as an Administrative Law Judge.

After Notre Dame, Kenneth went on to join Jimmy Carter’s gubernatorial administration in Georgia. He worked in a new inter-governmental relations unit, which connected State agency officials with Georgia’s congressional delegation in Washington, D.C. This helped to ensure that more of the state’s needs were being appropriately and effectively represented in Congress.

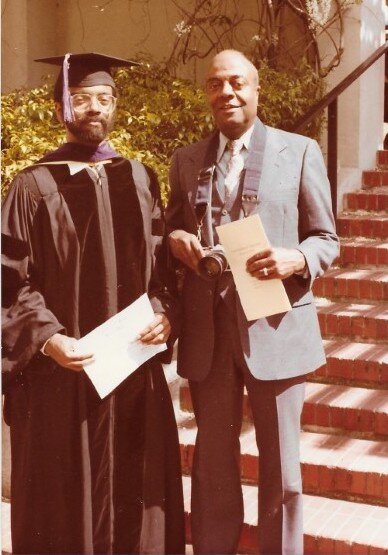

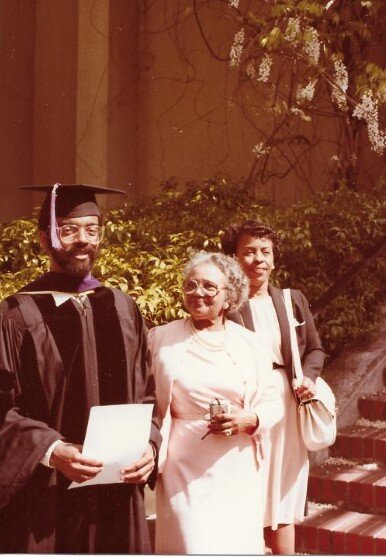

During this period, he began to realize that prestigious academic programs and opportunities for advancement were limited in his home state. In 1976, after being accepted to law programs at Georgetown, Boston College, and NYU, he decided to attend the UC Berkeley School of Law. Kenneth was one of just a few students from the South in the entire school. His experience working with Carter, the soon-to-be elected President, ensured that Kenneth was very well-known within his class. In his final year of law school, he effectively parlayed this influence to help elect a gay, Black classmate as student body president.

After practicing law in Los Angeles for a year, Kenneth moved to NYC, where he found many others living their lives the same way as he did. Kenneth ultimately ended his career as an administrative law judge. This role allowed him to fight for justice and equality by penalizing individuals who committed racist acts in violation of public health and environmental control laws.

Kenneth outside his office as an Administrative Law Judge in NYC.

One incident in particular stands out to him. Two white men drove a dump truck into a Black neighborhood in the Bronx and dumped the contents of their truck right in the middle of a cul-de-sac —while a Black wedding was being held in the backyard of one of the homes, no less. Residents chased the truck down the street to capture its license plate number and file a report with the police. The two men later came before Kenneth expecting to pay a minimal fine. But, he handed down the maximum fine of $25,000, citing the discriminatory nature of their actions.

From his early days marching in the streets of Atlanta to the courtrooms of NYC, Kenneth’s steadfast commitment to justice is his living legacy. “I was going to be true to myself,” he recalls. “I was always going to be a force for change.”

And that he is, without question.

Kenneth at his graduation from UC Berkeley School of Law with his father, Kenesaw Mountain Landis Mannings, and his grandmother, Ann Nixon Cooper.